|

Volume 1: The early years 1948-1966 Volume 2: College, Army, first jobs 1966-1977

|

Volume 3: PC Revolutionary: Computerland, Beehive, Novell 1977-1989 Volume 4: Beginning The Great Panic: Divorce, bankruptcy, mid-life crisis 1990-1993

|

Volume 5: Being a Sea Cucumber 1994-1997 Volume 6: Searching for a new life, 1997-2002 (and discovering how deep the Panic Scars are)

|

|

Volume 7: Recovering from Panic Thinking 2003-2008 |

Volume 8: Remaking a home in the USA 2008-2010 |

Volume 9: Searching for positive feedback 2011- |

|

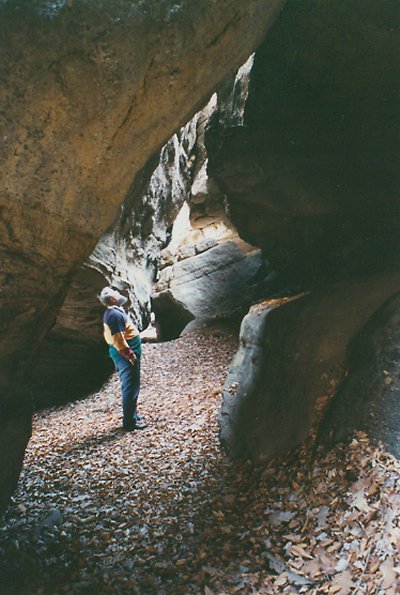

This is Nelson's Ledges State Park, well east and a bit south of Cleveland. The Nelson's Ledges Park -- an auto raceway -- is more famous locally, but this, the state park, has some wonderful cravasses and cliffs. |

|

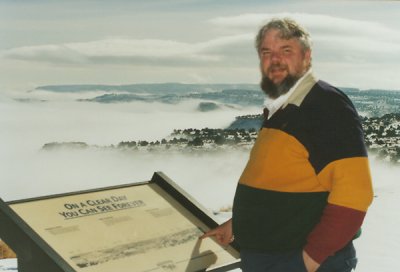

This is what a place like Zion National Park would look like, if Utah had more rain. |

In 1990 my life turned upside down. Never before, not even in teenagehood, had I felt the world around me change so dramatically; change in such unexpected ways; and change so badly for me. It was a "jawdropping" era.

On the good side, I see a "digital darkroom", and that's the inspiration to take up photography again.

The crisis began as two clouds started growing on my horizon. The first cloud was over my marriage, and the second over my career.

Sue and I loved each other. But love wasn't the foundation of our marriage. We had lived together in love for six years before we got married, and been happy.

Sue was the first to "pop the question". I don't remember when, but I do remember where: in her parents house in Bountiful, Utah. She proposed; I told her, "Maybe... some day in the future... but there is no reason to get married now."

She decided to stick with me.

In 1977, there was reason. I was ready to launch Computerland with her help, and we were both ready to have children.

I pointed out to her at the time that I said, "Yes.", and many times before and I after I said "Yes.", "We should not let this piece of paper [the marriage certificate] govern our relation. We are doing this only so our children won't be bastards."

To this she said, "Yes, yes."

But I sensed by her actions in getting ready for the marriage that she was just mouthing those words, so, two weeks before the wedding. I called the marriage off. Sue was hurt, but she chose to stay with me.

Six weeks later, we started talking marriage again, and this time she was taking what I was saying seriously. To emphasize the minimal part that the piece of paper called a marriage certificate should have in our lives, I suggested we elope and get married at a wedding chapel in Las Vegas. Sue agreed.

The foundations of our marriage were threefold: a mutual interest in work, a mutual interest in love, and a mutual interest in bearing children.

Between 1977 and 1988 those three pillars crumbled.

First, Sue had all her children by C-section, and when Roger III was born, our fourth child, that was the end. Bearing children required a marriage certificate, but raising them did not, so that pillar was gone.

Second, Sue and I were both vitally interested in Computerland, but running the Computerland was a wild roller-coaster ride, and after three years, we sold out. After Computerland, I went to work for Novell in Utah valley, and later Beehive, and later Novell again. Sue wanted to stay in Salt Lake City, so I commuted. My work changed about every three years, and so did Sue's, and by the mid-eighties we were no longer sharing occupational interests.

The "capper" to our differences in careers came when we got the Pultrusions windfall in 1988. Sue wanted to start a pizza business from that windfall. I had no interest in pizza (other than eating it); I would have rather invested in starting a software company, but I was not ready to do so at that time.

Third, our love interest was fading -- Sue was having a hard time keeping up. Intellectually and instinctively Sue still loved me deeply. But viscerally, and perhaps emotionally, she was having a hard time showing it -- other needs besides "keeping her husband happy" pushed up higher and higher on her priority list.

Instead of wanting to make love, Sue would want to make phone calls. Gradually, she started calling more and more people, more and more times. The times most frustrating for me were when we came home from a movie. Throughout our early relationship, going to an afternoon or early evening movie and following it up with some sex was one of life's great pleasures. But by the late-eighties, Sue would race for the phone when we came home, and make sure she stayed on long enough for me to get discouraged.

I was frustrated at first, but I evolved into resigned. I took her actions as a sign that "times were a changing", and that if I wanted romantic love, I was going to have to find it elsewhere.

Romantic love has always been important to me. Sex without a mutual feeling of attraction on other levels is repugnant to me. It's ugly.

I, perhaps, could have looked hard for a lover, but that didn't sound terribly appealing. I don't like keeping secrets, or living lies, or making my life unnecessarily complicated. And, I was only half done with my family raising plans. So, divorce and remarriage looked like a much better solution to this looming dark cloud than finding a lover. In my vision of what would happen, I would become a "serial polygamist", heading up two families. I would love both families and my wife and ex-wife -- but in different ways, ways that were compatible with the affections they wanted to show me.

|

More from Nelson's Ledges. |

|

This is a Beech tree root, one of several where the roots climb over the cliff edge and into the soil below. How they managed this, I don't know. |

When I first got into the personal computer industry in 1977, I could "get my arms around" all that was being done in the industry. While running Computerland I had assembled computers from kits, learned to do some programming in BASIC and Pascal, and mastered WordStar and Visicalc, the "killer aps" of their day.

But as the industry grew, the "Cornucopia Effect" kicked in -- the industry got bigger than my "span of competence", and I had to make choices as to which areas to pursue further and which to give up on. For instance, when I joined Novell, I concentrated on LANs and software that made LANs work better, and gave up on trying to master all kinds of word processors and spreadsheets.

When I joined Beehive, I gave up on LANs, and learned about protocol converters and IBM 3270 networks.

When I rejoined Novell, I was back to LANs again, but now the LANs were getting bigger and more complex. At first my diverse experience, and my recent experience with protocol conversion worked in my favor. This period -- from about 85 to about 88 -- was one of the real fun periods in my work career. I had just received my MBA, and I was contributing to Novell as an article writer, a pundit, and a liaison with software developing companies. I was one of the few people on the Marketing side of Novell who actually enjoyed talking with the engineers, and could share their hopes and dreams for the product.

But by the late eighties, I was again being stretched by the Cornucopia Effect, and Novell was moving the Netware product in directions that I didn't want to go in my personal growth. When Novell introduced Netware 4 with Directory Services, I could see lots of complexity being added to the product by Directory Services, but with little benefit to end users -- the beneficiaries of Directory Services were those who administered very large networks, no one else. What I wanted to see was a Netware that was well-adapted for smaller, distributed installations, and real easy for end users to install. This put me out of step with the company -- by the mid-nineties Novell thought so much of the Directory Services concept that they time and time again "bet the company" on it.

As Novell and Netware drifted into servicing complex networks, this left me with trouble seeing where my "next step" would be. I had hitched my star to Novell, and risen quickly with it, but as Netware changed into something I wasn't interested in, I was feeling distress. My last project at Novell was becoming an expert on what it took to have PC's and Mac's share the same LAN, but this turned out to be a niche market, not a mainstream one.

Adding to my distress, in late 89 there was a "palace revolt" at Novell, and by the end of the crisis, the visionaries were leaving. The visionaries were symbolized by Craig Burton and Judith Clark. Ray Noorda, the president, remained in charge of the company, and as the visionaries left, he put "the sharks" in charge.

Within six months of their leaving, I was maneuvered out of the company by my immediate boss -- one of the new sharks -- and I was real unhappy about it. I felt he had betrayed me. The good news was I teamed up with Craig and Judith shortly after I left, and got paid well to do so; the bad news was that teaming up lasted only six months or so.

But, it was while I was working for Craig and Judith that my divorce became a reality, and the fact that I had a good paying job as I divorced was to have terrible consequences.

I first talked with Sue about divorce in 1987, but didn't push it. I wanted Sue to "buy in" to the divorce idea before it happened. That would be a good sign that we were on the same wavelength, but, sadly, it never happened. Time and time again we ended up arguing over money. Sue wanted lots of money, and over a long period of time. She, in effect, made divorce too expensive for me.

In some ways this was ironic. It was ironic because we had never earned enough money to sustain the family lifestyle. Sue had the kids in private school and we were paying for a house. We managed to get by during the eighties because of periodic windfalls that would come to us, mostly from the Bourke-White estate.

In 1987 I remember being particularly worried about this. I looked at my income, and I looked at our lifestyle, and they just weren't long-term compatible.

But in 1988 a potential solution to our problems came along: a huge windfall from the sale of Pultrusions stock. This was stock that my father had given my brother and I when it was near worthless. A few years later the company turned around handsomely, and then was sold. We got $330,000 from this, before taxes.

"This" I thought, "is enough to buy me a divorce." And it should have been.

But Sue didn't see it that way. She felt that the windfall had come, "to the family" and that if I wanted a divorce I was still going to have to pay her lots of money for a long time out of "my share" of the windfall, which would be one sixth.

It was crazy logic, so once again we couldn't come to terms, and the divorce didn't happen.

What happened instead of divorce was that Sue came up with several projects to spend the money on: new cars, doubling the size of the house, and launching the pizza business (mentioned earlier) with a girlfriend partner, not with me -- our pillar of mutual business interest was truly completely crumbled. She also came up with a tax advisor who came up with a way to substantially reduce our tax payment.

By 1989 all the money in the windfall was committed, and then the walls came tumbling down. Sue had tackled too many projects, and when the pizza business hit yet another crisis she had a nervous breakdown and was hospitalized for a month for depression.

.... I couldn't save the pizza business, I don't think anyone could have. I tried to, and as I looked closely at what Sue had been doing, I found that for months and months the expenses had been too high and the sales too low. This was like what we had experienced at Computerland, but not even a little profitable, and with no plan for what to do if things got rocky. With Computerland, we had a sell-out strategy, and we actually got out with a modest profit. With the pizza business Sue had already committed all her resources -- all the family's resources -- before she would recognize the business was in crisis. There was no money left; vendors were threatening; taxes had not been paid; there was no way out but to try and shut down the businesses as gracefully as possible over the next month.

Jerry, Sue's brother, and I did that, but it was a thankless task, and Sue never thanked us. After she got out of the hospital she told us we had given up too soon. My jaw dropped. In one year our financial status had been transformed from a net worth of over $200,000 to a net worth of -$200,000 ... and Sue sincerely believed we had stopped too soon? (She was sincere in this belief. A few months after she got out of the hospital she started up another pizza business, but that folded, too.)

The financial disruption was too much, we filed for bankruptcy. GOD! A bankruptcy! Never in my wildest dreams.... I was bankrupt! Sue may have come from a family that lived on the fiscal edge, but I did not. I was a saver, THIS SHOULD NOT HAVE HAPPENED!

But there was worse news on the horizon: after the bankruptcy was completed, the IRS decided not to agree with Sue's tax advisor on the reduction in our 1988 tax obligation. The tax advisor had subsequently died of a heart attack, so I was on the hook for a $20,000 IRS obligation as well, which, after penalties mushroomed to about $40,000. In addition, the student loans from while I was getting the MBA had not been cleared by the bankruptcy, so at added more thousands of dollars of uncleared obligations.

|

A smoke plume over the Kennecott Smelter in Magna, Utah, west of Salt Lake City. This was shot from an I-80 overpass on a stinking cold morning in January or February in the mid-eighties. |

|

The Big Dipper star constellation, shot on the Alpine Loop on a moonless

night. This was not an easy shot. It was done with a simple tripod and

ISO 400 film. The key was find a road that would have no cars coming by

long enough for me to make this exposure (about 15 minutes).

I've made many attempts to shoot this kind of shot, only a few have turned out well. |

Fortunately, Sue finally agreed to a divorce.

Unfortunately, in spite of the $330,000 that I had just brought into the family, in spite of the fact that she had just squandered all of that, she still wanted lots of money from me.

My father was also urging and advising me to "be responsible". It was clear that he meant I should give a lot to Sue.

I looked at my income from Clark-Burton, made some optimistic assumptions about my future income flow, and agree to pay Sue $1500 a month in child support.

I didn't like the settlement, and I said so many times. It was a huge amount, about 30% of my income, and with the government taking another 30%, it didn't leave much for me -- and I'm a very self-serving person. If I'm not making money on a deal, why should I be pursuing it vigorously?

I was also still profoundly upset that Sue showed no remorse and felt no responsibility for the money she had just squandered (to this day she never has, and to this day I hold that against her).

My only hope for making this plan work -- for making my own future comfortable -- was that my income would grow steeply.

Things did not go optimistically. Shortly after the settlement I was laid off from Clark Burton, and shortly after that, I got the notice from the IRS that they wanted another $20,000.

The house of cards completely fell down, and my life and career started into a power dive.

Editorial on the Divorce process in the US

Every preventive social system is built to combat an image. For instance, Smoky the Bear is the image for forest fire fighting, the War on Drugs was fought to eliminate the drug pusher who hung around schools, and Homeland Defense is built around preventing a repeat of the Sept 11th disaster. The divorce and child support process in the US is built around the image of chasing down the "Deadbeat Dad".

All of these images miss the point, and the point is that the social phenomenon being combated is much more complex than these simple symbols portray. Because they miss the point, expensive mistakes are made. Controlled burns are still a controversial policy for forest fighting. The War on Drugs made the prison system an American boom industry, the War on Terror has decimated the airline industry, and the Deadbeat Dad image ground up my domestic employment career for a decade. All of these, except forest fighting, have also been very hard on American civil liberties. All of these mistakes have reduced the quality of American living by a lot. In my case, I got enmeshed in the gears of the Child Support system, and I got ground up and spit out by them.

As I mentioned earlier, I was very unhappy with the divorce and child support settlement. I was unhappy because everyone was forgetting a key component in this settlement process.

What was that key component? OK, Happy Campers, it's game time. See if you can figure out!

First, let me tell you what people were concerned about, and see if you can guess...

And the key missing component ??? The envelope please..... [rrrip]

The key missing component is: ROGER WHITE'S INTEREST, why... that's me!

All these people and organizations presumed, a priori, that I was going to continue to work hard and make a lot of money, even if I was going to personally get very little for my effort.

Add to this a couple of IRS judgments, and whoa... I WAS GOING TO BE WORKING TEN YEARS... FOR NOTHING! Literally for nothing. I would have nothing saved after ten years of hard work, and I would be living at a poverty level all during those ten years.

Wrong!

Hey! If I want to live impoverished, I can to that without all the work.

For an example of the callousness: About three years after I lost my job at Clark Burton (and never replaced it with even half that income) I got a hearing notice from Child Support about the back child support I had piled up. I explained my situation to the lady case officer -- that I had had no money and little income since the settlement was signed -- and once again I was ignored. Seriously ignored this time: she chose to slap a $15,000 judgment on me for back due child support.

Did that judgment get that lady case worker any money that day?

No.

Did it ever get the Office of Recovery Services (child support people), or my children, or anyone, any money?

No.

Did it keep me from making money?

Yes.

Did it complicate my subsequent settlements with Sue?

Yes. <sigh>

I found myself thinking of the Sea Cucumber on the tidal flat. I had been picked up by ex-wife Sue and the ORS searching for a Deadbeat Dad. I was stiff, and when they prodded me I squirted money. They squealed in delight and prodded me some more. I squirted more money, but now I was floppy and droopy. I had no money left. They kept prodding, and I spewed my guts. My only hope now was that they would lose interest and discard me.

Why was my poverty bad? Why would it be a good thing if I had money?

For two reasons:

The first was to get back me on my feet, after the unprecedented bankruptcy and IRS judgment. I was used to living a $30,000 a year lifestyle, and if I could maintain that, I would work for it. But, again, the circumstance presented to me by Sue, Child Support and the IRS were such that I had two choices:

Since I was not given the option of living a $30,000/yr lifestyle on a $40,000/yr income -- a reasonable expectation -- and I could not land a $100,000/yr job, I began my education in earnest on how to live on $10,000/yr. It was a wrenching experience, and Nietchez is wrong: that which doesn't kill you doesn't necessarily make you stronger, it can make you brain-dead instead.

And, this experience was really bad for the community. What benefit did the community see in having me take my attention and resources for many years to learn how to live on $10,000 a year? What a waste!

The second reason was, if I had money, I could have the confidence to make more money. If I had been able to follow through with my plan, and been able to take a couple years to work my way up to a $100,000/yr job, and been the head-of-household for two households, Sue and her children would have gotten a lot more money from me in the long run, and a lot more non-monetary support -- I would have been around and a good example for her family. Ironically, the safeguards set up by the system to discourage the Deadbeat Dad were encouraging me to be the Deadbeat Dad.

In summary, the current divorce and child support system, and the community, completely ignore any difficulties the support giver may be having during this period. In my case, all this ignoring lead to personal catastrophe. This should be changed.

|

I was faced with a bifurcated income choice: if I earned $100,000 a year, I would do OK. If I earned nothing a year, I would do OK. But if I earned $40,000 a year, I would be eaten alive by people hunting me down for money.

This is not the kind of choice our community should force on a post-divorce child supporter.

|

On the way to Delicate Arch, you get to walk over this neat suspension bridge. (winter, late-1990's) |

|

Rock Surfing at Arches. This is on the path to Delicate Arch. They don't call this Slickrock Country for no reason! |

|

Utah Capitol, looking roundA view of the main gallery of the Utah Capitol builing, using a fish-eye lens. |

I knew that this combination of divorce, job loss and bankruptcy was a huge personal crisis. I knew it had to be dealt with quickly. It was life-threatening. I live for two things: my family and my work. Here I was without either, and without work I was also without health insurance. I knew I was in shock over how badly this had all turned out -- Going from +$200,000 net worth to -$200,000 worth in less than a year -- and even less worth now that I was saddled with a hefty child support payment.

I was in a Panic: a panic without adrenaline, but a panic nonetheless. I focused down and became single-minded.

The plan I developed to get through this crisis was simple:

What did I sacrifice in this focusing down plan? The evolving of my career into a professional pontificator and my science fiction writing. Thinking about them became impossible until the "Panic Plan A" (the four point plan above) was completed.

The plan was a good plan. It was simple and straightforward and it would get me what I wanted.

<Sigh> The plan ran into difficulty on Step One.

As described in the editorial above, Sue, Child Support, and later the IRS, were determined to strangle their Golden Goose: me.

For a year I tried hard to land the 100 K/year job that would get me out of this pit, but it just didn't happen. While I was doing that, I didn't look seriously at 40 K/year jobs because they wouldn't solve my problem.

After a year of no results, I finally said to myself, "Screw it, this isn't going to happen." And I moved seriously on to Plan B, the no income plan. I would have to survive on no income for seven years. Then the statute of limitations would run out on some of my debts, I could file another bankruptcy, and Roger III would be eighteen, which would end my child support obligations.

There was one other surprise that divorce revealed: Sue's self-destructiveness. Time and time again I pointed out to her that some choices she was making during the divorce process were not only hurting me, but hurting our kids and her as well. Time and time again, she chose against me because of a "you can't trust him now" instinct -- an instinct that I'm sure was fanned by the advice she got on how to handle a divorce. This was another jawdropper for me -- she could not be counted on to act in her own best interest, or the best interest of her children.

An example that I remember poignantly: at the time of the divorce we were still carrying a hefty term life insurance policy on me that dated from Computerland days. I asked Sue if I could take that policy, and leave her and the kids as beneficiaries until I set up some new relation. The policy had been started some eleven or twelve years earlier, so the premium was quite low compared to what starting a new policy would have been.

Sue said, "No. I want to keep it."

"You're sure?" I asked, "It's kind of expensive. Will you able to keep up the payments?"

"Yes, I will." she said.

Two months after that conversation, I received a letter in the mail notifying me that the policy had expired for lack of payments. <sigh> Yet again Sue had cost the family a big chunk of wealth... self destructive!

Sue had warned me many times when we talked about divorce that, "Divorce will be expensive for you." I didn't realize that she was saying her own self-destructiveness would increase the cost tenfold.

I was still in love with Sue when I asked for the divorce. Again, my plan was for serial polygamy, and I was assuming that -- as we agreed upon when we got married -- the "piece of paper" was not determining our relationship, it was only a license to bear legitimate children. I wanted the divorce to be simply another "piece of paper" that would let me develop a legitimate relation with another woman and bear more legitimate children. I didn't want the divorce to change our relation, and, if the first piece of paper hadn't been controlling our relation, this second piece of paper would not have, either.

It was only as the divorce process unfolded, that I fell out of love. It was only after Sue:

It was only as these blows kept striking me that I fell out of love with her.

I am occasionally asked (and once in a while I ask myself) if, given the catastrophe that followed, the divorce was a good idea.

The answer always has been, and is now: Yes.

First, the catastrophe was not so much the divorce as it was the handling of the Pultrusions Windfall. The windfall was a powerful tool, and Sue and I used it so poorly that we injured ourselves badly.

Second, the divorce demonstrated how much Sue had let "that piece of paper" come to determine our relationship. She had completely forgotten what I had told her when we got married -- that for us the marriage certificate was only a license to bear legal children, no more. After the divorce we had little to do with each other, which meant that during our marriage our lives had de facto drifted apart, and for the last few years of the marriage only the piece of paper was holding us together.

A relation held together by only a piece of paper is not the kind of relation I want with "my woman." Painful... painful as it has been, the divorce was a good idea.

And finally I will give you a Roger White Truism:

|

If you think it's tough to know your future wife, think about how tough it is trying to know your future ex-wife. |

|

I took this picture and this picture, and made... |

|

My first digital darkroom creation. (See more in my photo tips section) |

In 1991, I saw digital darkroom system at a trade show. It was hugely expensive -- probably $20,000 -- but I had seen it. I was confident that the cost of what I saw would halve each year, so in 1995 I could afford one. This was a great inspiration: I could take up photography again.

After MIT, my photo-taking had declined dramatically because I no longer had time to putter around in a dark room. Color photography gave me very little control over my images compared to black-and-white photography, and I was real unhappy with the washed-out prints I got when I sent my black-and-white film into commercial processors.

In 1992 I actually got a chance to play around with for a couple days with a digital darkroom system based on a Macintosh computer, and I was so excited that I dusted off my cameras.

In 1992 and 1993 I got out and seriously photographed Utah, in color. I was building up a library for the digital darkroom to come.

But, it was easy to shoot a lot more than I could afford to develop. (These days came during the heart of my divorce/bankruptcy financial crisis) Marty and I went on photo expeditions, and we started defining the success of those expeditions in how many rolls of film we shot. A "one-roller day" was hardly worth the effort. A "three-roller day" was a satisfying one. We used 36 exposure 35 mm film, so a three roller day was about 100 pictures.

I stored exposed rolls of film in my freezer. I didn't get a chance to develop them until I got to Korea, and by then I had a huge bag of film.

An exercise in mental frustrationI distinctly remember the first time I dusted off my Mamyia TLR (twin lens reflex) camera to do some nature photos. I was visiting an extinct volcano park in New Mexico on a trip to a trade show in Dallas. I started doing what I had always done ten years before... look for a shot, check lighting, set exposure, set shutter speed, frame, and shoot. But... I found I was getting... enormously frustrated. After forty minutes of that, I was about to cry in frustration!

I quit, and started driving on to Dallas, and I soon felt better. I though about what I had been feeling. What I was feeling was "sore muscles" in my brain: photography was something I knew I knew how to do, but I hadn't done it for so long that most of the "details" of what to do were "in archive" -- not in the active part of my brain. The frustration I was feeling was the strain on my brain of trying to pull this "how to do it" information out of archive too rapidly.

I did another nature photo session the next day, and I was quite comfortable.

|

The Brain ArchiveJust like a computer has RAM and hard disk, the brain has active and storage parts of memory. And, just like on a computer, it can take some time to get information out of the archive.

This hit me most vividly one day as I was walking through the parking lot of a fast food restaurant near Novell.

I had walked out when a man came up to me and said, "Hi Roger, how are you doing?"

He knew me, and I vaguely knew the face, but that was all I knew about him. My brain's "Rolodex" started spinning furiously to bring me up more information.

We talked platitudes for about a minute, and my Rolodex was still pulling up nothing! I concentrated on Novell faces... nothing.

We talked for five minutes, and I could pull up nothing on this person! Incredible! Incredible in two senses: first, that I could remember nothing about this person, and second, that I could talk with him meaningfully for five minutes without knowing anything about him! Finally, as we were parting, he mentioned Toastmasters. Ah... the first piece of information came up from my archive: he was a Toastmasters attendee at the Salt Lake library Toastmasters.

The second piece of information came up: he was very boring, and I'd forgotten all about him because there wasn't anything about him worth remembering.

For the next three days, my brain archive popped up more and more stuff about this guy. Internally I was saying, "Yes.. Yes... But now I want to forget him again." And my brain archive would reply, "OK.. But wait! Here's something else about him..."

Maps, by the way, are almost always stored in archive. This is why when you ask a person for directions there's usually and lot of "umming" and "awwwing" before you get an answer.

|

While I was looking for my $100K a year job, I investigated what I could do on the "gray market" -- doing work for unreported income. I didn't find much, but I found writing was my most bankable talent, and several months after leaving Clark-Burton I teamed up with some ex-Novellians who had started a company called Network Technical Services (NTS). NTS wasn't gray market, but the work was definitely erratic. It consisted of Dave Doering and Barbara Hume, and almost Ed Liebing -- he had founded NTS, and just departed NTS to return to Novell. (NTS later became Techvoice.)

Erratic as it was, NTS work was the best I could find. I wrote magazine articles and white papers. I interviewed people and did a lot of experimenting with new, Netware-related products produced by third parties.

I did this for several years and the work went modestly well. There was never enough, and I committed some gaffs during that period -- so I remember it as only modestly successful work. During this time I got my first CNE (Certified Netware Engineer) certificate, and looked hard at getting a Certified Netware Instructor (CNI), but backed off -- it was a lot more work, as I recall.

As I became more established at NTS, I moved back to Provo. I did this for two reasons: to get closer to my work, and to get further from Sue. Sue was developing a nasty habit of depositing the children on my doorstep with about two hours notice, and leaving them for days. She would say, "Keep them a couple days." And mean keep them a week. The kids were very good, but having to tend them would play hob with my writing schedule. And when my work came in late or hasty, my reputation as a freelance writer suffered.

Finally, in 1993 three things came to a head:

It was time for something completely different, and I looked around for something different to do, something that would widen my perspective of the world again, and give me new inspiration.

I looked around for what I could do that was completely different, and found myself heavily constrained:

Given that I had been continuously looking for work since 1990 and before, that last constraint was a "real lu-lu." I was just not finding many people who wanted to pay me to work, and this was getting scarier and scarier.

What I came up with was originally inspired by Marty's adventures in China: what took him over there first was teaching English conversation.

I looked into teaching English conversation in China and Japan. As I was looking I spotted an ad for teaching English conversation in Korea. Korea.... it hadn't even been on my radar when I had started looking, but I knew where it was, so I arranged to talk with Mr. Tok-han Kim who was visiting the US.

I liked what he had to say and he liked what I had to say, and in November 1993 I was flying for Seoul, South Korea to spend a year teaching English conversation in Suwon, Korea.

The job's benefits:

The downside was I would have to live in a strange land for a year. I steeled myself for another Vietnam experience, and plunged ahead.

|

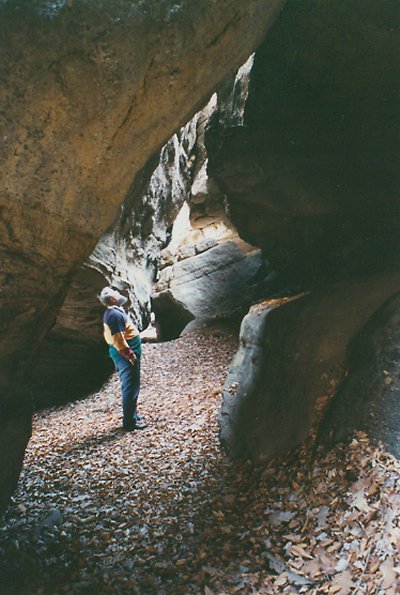

Once I saw the digital darkroom, I traveled Utah to build up a library of shots I could work with. This is southern Utah on a winter morning. Even though Utah is a very dry place, thick fog is common in the winter. |

|

Adrienne on Mount Olympus, part of the eastern border of the Salt Lake

City valley. (fall 1993)

This was taken a week, or so, before I first traveled to Korea. 30 minutes after I took this shot, I slipped, fell, and broke my Nikon camera. I was devastated, I was thinking to myself, "Which would have been worse: breaking my camera or breaking my ankle... if I broke my ankle it would heal all by itself, but now I'm going to have to find money to fix my camera." |

|

Roger on Mount Olympus. |

Being best in the world

It's a nice feeling being the best at something. In 1992, in the depths of this terrible panic, I found I was not only the best at something, I was the best in the world at something!

While I was writing technical pieces for Techvoice, I was also writing computer gaming reviews for Computer Gaming World magazine, and this was a nice excuse to play a lot of computer games. The hot multiplayer game of that era was Command HQ (CHQ) written by Dan Bunten. It was a one-on-one game, played by connecting modems -- crude multiplayer by later standards, but it was the best multiplayer game out in that era. Our gaming group in Salt Lake played a lot of it, and we discovered there was a CHQ forum on Compuserve (a predecessor to AOL, which was at this time a predecessor to The Internet). On CompuServe I became known as Roger-Tsu (after Sun-Tsu, the Chinese general who wrote the first military history book: The Art of War.) And I posted The Sayings of Roger-Tsu on the CompuServe forum -- my first on-line essay, and it was well-read by fellow CHQ players from around the world. The Salt Lake gaming group became known as The Gang of Three (myself, Richard Block and Marty Prier).

In 1992 the first CHQ tournament was organized by the CHQ Forum members on CompuServe About fifty players participated from around the world. The Gang of Three all participated as individuals, and I made it to the finals.

The final match was between me and a protégé of mine who lived in Alabama: Grasshopper. It was a best of three contest. I won the first match; he won the second, and then came The Nuking of the Narwhals Incident.

By game three I was totally exhausted. We had been playing three or four hours to complete the other two games. I proposed a break, but Grasshopper wanted to keep going. The good news for me was that Richard and Marty had both come over to watch this match, so I'd been getting advice and moral support.

I lost the toss, and Grasshopper chose to play the 1986 scenario -- the most complex, and the one that included nuclear weapons. I groaned: this was the scenario I dreaded!

The game started and our positions evolved. It was a close match, but I was losing ground. Finally, I said, "That's it. My mind is totally fried. One of you two take the mouse." And Richard slipped into the seat as I slipped out. Richard did some fine recovery, but Grasshopper was still gaining ground.

We three finally decided that -- dicey as it would be -- we had to drop a nuke. In this game, the good part of nukes was they destroyed everything in their blast radius. The bad part was that people of the world were so repelled by the idea, that many troops and provinces would desert the nuke dropper. The added twist was: how many depended on where the nuke was dropped, and if it was the first, or not.

Richard carefully lined up the mouse for a drop in Central Europe, where a large cluster of Grasshopper force was threatening to move west....

Then, somehow, just as he clicked to drop, the mouse jerked... and the nuke went off over the Greenland Sea! He hit nothing!

A few provinces changed to Grasshopper, and Richard's concentration was totally blown! He got up and walked off, and Marty took the hot seat.

Well... now that we had drawn first blood, Grasshopper felt safe in using his nukes because the worst changes happened to the first user of nukes. He launched a nuke into Central Europe to finish off our large cluster of forces defending western Europe! (ironically, very close to where Richard intended to drop.)

But, what a difference there was in world opinion about his drop! He did a lot of damage, and hit a heavily populated part of the world -- a dozen provinces changed hands, and some critical military units, too. After his drop, we controlled the oil wells of the Middle East, and in two minutes he went into an oil crisis! (all his units started moving slowly)

We held on to those oil wells like bulldogs. He tried another nuke, and it just got worse for him. The end came shortly thereafter. So, in the end, Richard's "Nuking of the Narwhals" had turned out to be a brilliant game winning tactic, and Roger-Tsu became the World's Best Player of CHQ!

In the depths of my personal, career and fiscal crisis, I found I was the world's best at something, and whenever I think about this, I find myself humming the Beatles tune, "I get by with a little help from my friends."

|

|

Altair at Delicate Arch. |

|

Volume 1: The early years 1948-1966 Volume 2: College, Army, first jobs 1966-1977

|

Volume 3: PC Revolutionary: Computerland, Beehive, Novell 1977-1989 Volume 4: Beginning The Great Panic: Divorce, bankruptcy, mid-life crisis 1990-1993

|

Volume 5: Being a Sea Cucumber 1994-1997 Volume 6: Searching for a new life, 1997-2002 (and discovering how deep the Panic Scars are)

|

|

Volume 7: Recovering from Panic Thinking 2003-2008 |

Volume 8: Remaking a home in the USA 2008-2010 |

Volume 9: Searching for positive feedback 2011- |